EX Special Report: Did Starfield suck?

Bethesda’s seven-years-in-the-making space RPG Starfield finally came out on Sept. 6, and public opinion has been sharply divided. At EX headquarters, our opinions also diverged — at least when it came to in-universe food brand “Chunks.”

Chris Breault: Pao! We’ve both been out in the star field for weeks. I’ve been mining ore and running chores. I’ve been inhaling space drugs at crummy space hotels that have one guest room per floor. I’ve put in the hours to finish the main plot and all faction questlines, earn a Class C license, and build a starship that looks like a Best Buy. And I have just one question for you: is this game a piece of shit or what?

Pao Yumol: Oh, it’s a piece of shit all right. It’s not a GOTY contender for me. It did, however, help elucidate the genuine joy I derive from Bethesda’s haunted open worlds, their oozing warts and blemishes included.

How did you spend your dozens of in-game hours?

CB: I spent a lot of time warping to planets, bunny-hopping 500 meters to a mission site, then shooting some guys and retrieving an item. (They always waste your time by tacking on a 500m hike.) Then I warped back to whoever asked me to get the thing. I have the same issue with this that everyone else already pointed out — you return to these laggy fast travel menus and repetitive “liftoff” cutscenes every few minutes, and the stretches of real game in between often don’t feel long enough.

The Bethesda games that I’ve returned to a million times (Oblivion, Skyrim, the Fallouts) were laid out in a way that made it impossible to see everything. You start walking one direction with a certain goal, you get distracted by a tower you see in the distance, inside the tower you find a book that gives you a recipe that requires butterfly wings, you start running around looking for butterflies and you get ambushed by a bandit who’s carrying a note that gives you a quest, and so on for 80 hours. You wind up chewing this unique termite path through the game, and you run into enough random handcrafted bits amid the copy-pasted dungeons to preserve the illusion that there’s always one more thing hidden somewhere that you’ve never seen before.

Starfield is the only post-Morrowind Bethesda game I’ve played that doesn’t have that loop. (I skipped Fallout 76.) Wandering between points of interest on most planets means crossing a barren wasteland at a snail’s pace. The random POIs seem to be a tiny set of copy-pasted locations (like a construction site guarded by robots that turn hostile if you enter the office where you can easily switch them off). It takes less than an hour to dispel the open-world illusion that games like Oblivion and Skyrim have maintained in my head forever.

Another example: there’s a computer you access in the course of the Crimson Fleet questline to find the location of a long-lost spaceship full of cash. But this terminal’s notes also pointedly describe another money ship that went missing around Saturn. This seems like an obvious breadcrumb for a Bethesda-style game to plant — a nice organic lead-in to a sidequest instead of an on-screen pop-up. And if you wander around Saturn’s moons, you can actually find multiple “ship crash” POIs. However, they’re all the same copy-pasted ship crash playset, and it’s one you see repeated across the galaxy; it has nothing to do with the treasure ship. It’s like Starfield nudges you to perform this scavenger hunt that only forces you to confront how repetitive the game really is.

PY: To be honest, I consider repetitiveness to be one of Bethesda’s original sins as a cosmic weaver of open worlds. I always found it telling that they leaned so much on procedural generation in order to pad out the first two Elder Scrolls games, Arena and Daggerfall; over time, this has become illustrative of just how much they tend to prioritize quantity over quality, surface area instead of depth.

Even though they went the hand-crafted route for every title since Morrowind, that philosophy has remained a consistent force in their games. The nearly identical spacer-infested Starfield outposts feel like the nearly identical radroach-infested Fallout vaults, only at least in Fallout 3 you’re likely to be treated to a “bottle episode” that attempts to use environmental storytelling to capture some semblance of a narrative arc within a single map. Sure, there are a couple of equivalents across Starfield’s various mystery starships and remote outposts, but they feel fewer and farther between when spread across a map the size of the universe.

To that end, we’re both on the same page about the faction questlines surpassing the majority of the other available quests in terms of writing, variability, world-building, structure — just about everything. The faction questlines throw the rest into stark relief, highlighting just how skeletal and predictable city errands, bounty hunts, and smuggle runs tend to be. All the intricacies of the game’s interplanetary politics and differing cultural attitudes seem to have been reserved solely for main quests, faction quests, or the occasional companion-related excursion.

As a result, Starfield’s sci-fi worlds tend to feel half-baked when inspected closely — the corners of Disneyland’s Tomorrowland that get the least amount of foot traffic, where the paint chips and tarps are unceremoniously thrown over the busted animatronics. I identified dozens of missed opportunities in fairly boring item names like “alien jerky” or “penicillin x”; not nearly enough goofy compound words or cynical, hyper-branded imagery to meet my standards for a spacepunk dystopia. “Chunks” just isn’t that funny or imaginative as a name for processed food in the age of Soylent and SquarEat. I guess I’m more of a Nuka Cola girl.

This general banality also highlighted a number of anachronistic incongruencies that became more difficult to ignore as I waded further into the game. For example: Are people really still going to keep leaving scribbled pen-and-paper notes on their desk when nearly everything is stored in screens? If all money is crypto now, why can I still

”pickpocket” a thousand spacebucks off of some random bankteller? You’re telling me that, even in space, cigarettes are still more popular than vapes?

In one mission, I ransack an exec’s luxury suite and all I can think is: Why does this person own two copies of Nicholas Nickleby and nothing written after the 19th century? Did all art truly come to a halt when we left Earth behind? Also, you’d think paperbound books would only be of interest to enthusiasts or antiquarians in 2330 — what happened to tablets? Or, the eternal Bethesda RPG question: Why does everyone still play with standard playing cards when they only seem to own four or five out of the whole deck?

CB: As a longtime Bethesda fan I have to defend them on a couple things. First, I have many fond memories of Daggerfall, and I actually like the enormous honeycomb dungeons in it, which were completely impossible to find your way out of if you forgot to cast Recall at the entrance, because the game’s 3D auto-mapping tool always just showed you a giant convoluted intestine with no marked exits. There was a lot of variation in how big or scary or literally impossible to complete these dungeons were, which added an air of mystery.

Secondly, I’m actually a big fan of the Chunks brand. I like the Gourmet Chunks establishment you can find in the resort on Paradiso. I like the three red cubes on the logo and the fact that the restaurants pour a signature sauce on the Chunks. I wish you could do missions for Chunks corporate and get a novelty vending machine installed behind you in your cockpit like a sponsored streamer.

I don’t think there’s a lore answer to why there aren’t many artists around. I do respect the game’s huge wind-up to a tiny joke about Dickens — the bookshop owner in Akila City says she won’t buy any of his novels because he’s so over-represented among the books that people saved from old Earth, and his novels do seem to account for like 3/4 of the books found in-game. I have seen a few post-Earth books around, like Carrie of the Cosmos (published 2301) and the skill magazines. But as you suggest, authors and artists don’t figure much in the world of Starfield, which has a “fuck yeah science” cast full of physicists and doctors, plus a bizarre number of executives (the real heroes). The Astral Lounge DJ BorealUS is the only prominent artist I remember. I wouldn’t read too much into it, but it’s funny how much more of an artistic bent there is to Baldur’s Gate 3 — the bards Alfira and Volo, Oskar the painter, conscientious craftsmen like Dammon and Stonemason Kith, and Orin/The Dark Urge/various Bhaal cultists who see themselves as Hannibal-style murder artists.

As you said, the cities in Starfield feel kind of half-baked. They’re full of tasks to do, but there aren’t any real surprises that arise from something routine, like Cyberpunk 2077’s “Sinnerman.” There are a few areas I swear are some kind of band-aid solution that was meant to be fixed before release. The SSNN news “building” in New Atlantis isn’t an office tower, it’s a single room that you can walk into off the street; one of the network’s anchors is just standing in the center of the room, and another is doubling as the receptionist at a desk by the door. The Volii Hotel in Neon is another “building TK” situation: if you take an elevator up to floor two or three, you see a single guest room to your left, then a stub of a hallway that leads nowhere.

I can’t get over the fact that moving from Point A to B is just boring in this game. So many open world games have come up with their own solutions to this, whether by adding vehicles and traffic (GTA, Cyberpunk), radio (those games + Fallout), singing buddies (AC: Black Flag), or tons of recognizable NPCs with their own schedules (RDR2). But Starfield doesn’t even try to liven up your daily 500m jogs. It’s very relatable that the developers couldn’t figure out how to do land vehicles and had to make up a weird lie about it. But they could have at least matched Oblivion-era technology and given you a horse wearing a bubble helmet. None of those cosplay cowboys in the Freestar Rangers has a trusty steed?

PY: To your point re: Daggerfall and the scale of its dungeons — I never meant to imply that the use of procedural generation is an objectively bad thing! The roguelike / roguelite era has since given way to plenty of games that inspire awe by capturing a sense of randomly generated infinitude. It just signals a particular authorial intent to me if questlines are devised by algorithms and not written from scratch by actual people.

It’s Bethesda’s general philosophy towards quantity over quality that sometimes confuses me. In my view, Bethesda’s post-Morrowind open world games are caught between two aspirations: The desire to convey a linear narrative experience where “choices matter” (again: those faction questlines) and the desire to craft endless expanses that drive the player to bounce organically between points of interest. The former demands direct control on the part of the game’s quest designers — something that’s hard to achieve if dungeons and NPCs are mostly the work of procedural generation. The latter, however, requires both a massive amount of space and a high density of activities that can be approached non-linearly and on a whim.

From my perspective, that tension is exactly what’s to blame for the point A-to-point B thing you’re describing. Making sure every single planet is as lively and rich as Fallout 3’s Wasteland or Oblivion’s Cyrodiil would no doubt be impossible, even for a studio as big as Bethesda. So the game becomes stretched even more thinly; you dick around your first couple of planets or so, you reach the realization that Starfield’s ecosystems somehow never have more than three alien species on them at a time, and then you resign yourself to fast traveling pretty much everywhere, closing any barren distance between you and your waypoint as efficiently as possible.

As I got further into the game, I couldn’t help but think that, ironically, Starfield’s setting might be its biggest flaw. If the backlash to No Man’s Sky’s original release was any indication, audiences have enormous expectations for any game that evokes fantasies related to space exploration and colonization — a chance to venture into the “final frontier” with complete freedom, one of the primordial gamer desires, hearkening back to when Microsoft Flight Simulator blew people’s minds back in the ‘80s. It’s the reason why I think Starfield contains such a robust ship editor and features dozens of different angles for takeoff or grav jump cinematics.

Making a space exploration game is the closest to “mapping infinity” that a studio like Bethesda can get. It’s fitting for them to want to achieve something of that scale. But it also seems like a tall order for a studio whose latest game was so empty that it was deemed a “soulless husk” upon release. I wasn’t surprised that Starfield’s planets were so shallow, but I also still felt lightly betrayed — when I was really young, I wanted nothing more than to play a game where you could board your X-Wing in Tattooine, fly it all the way to a landing zone in Coruscant, then enter a bustling city full of lightsabers and Twi’leks and alcoholic milks of every conceivable hue.

Historically, enjoying Bethesda’s games has been contingent on whether or not I can embrace the loneliness at their center — that post-apocalyptic feeling where you’re the last living playable character in the whole world, running from imperial guards or listening to dead people croon over radio static, a wasteland where your mission is to kick over the rubble and determine what’s worth scavenging and what’s worth silencing with a dirt nap. But this loneliness was a bit easier to mitigate when you were groping blindly across a map for waypoints or info-rich NPCs, hoping to collide with a pack of bandits or freak vermin — not when you’re idly scrolling through the starmap to see which white or pink dot you’re supposed to jump to.

Also: I concede that My Life, Chunk by Chunk is a pretty good title for a Chunks biography.

CB: Thank you. In this house, we respect Chunks.

I want to go back to roguelikes for a second, because I think Starfield tries out some roguelike ideas (especially with NG+) but doesn’t really commit to them. Most roguelikes (Slay the Spire, Returnal, whatever) have enough risks and rewards built in to make the random variation in their layouts meaningful from run to run. But Starfield doesn’t have a solid economy or risk/reward mechanics; nothing is rare except for god roll guns that could drop from any mini-boss. No part of the game is tough enough to make the differences in its procgen landscapes matter to the player.

There’s a roguelike-like mechanic in Starfield where a random starship can land near you while you’re wandering around on a planet, and then you can run aboard and hijack it. It’s an air drop! Cool idea. Except most of these ships are fake. You easily clear out all the mercenaries on the ship and then when you go to the cockpit there’s a little pop-up saying the ship is “inaccessible” or you’re “not authorized” to fly it, even if you have the skill to fly everything in the game. Sorry, prop ship! It’s the most maddening cop-out in Starfield. They came up with this whole mechanic but couldn’t tune the difficulty of it or get the rest of their economy in order, so instead of the actually interesting reward (the ships in this game vary a lot) you get a few thousand creds from the glove compartment.

You said Starfield’s design felt torn between two conflicting desires; I was thinking of it more as two different games. First, there’s the galaxy of wonderment that Todd Howard hyped up as a passion project of immense scope; this turned out to be a second-rate No Man’s Sky with bad base-building and a bunch of fake mechanics like prop ships. The second game is a traditional Bethesda project that uses the first thing as a fragmented backdrop. I only ever wanted to warp between different setpieces in Game #2, but I was often forced to spend a few minutes hopping around or using the scanner in Game #1.

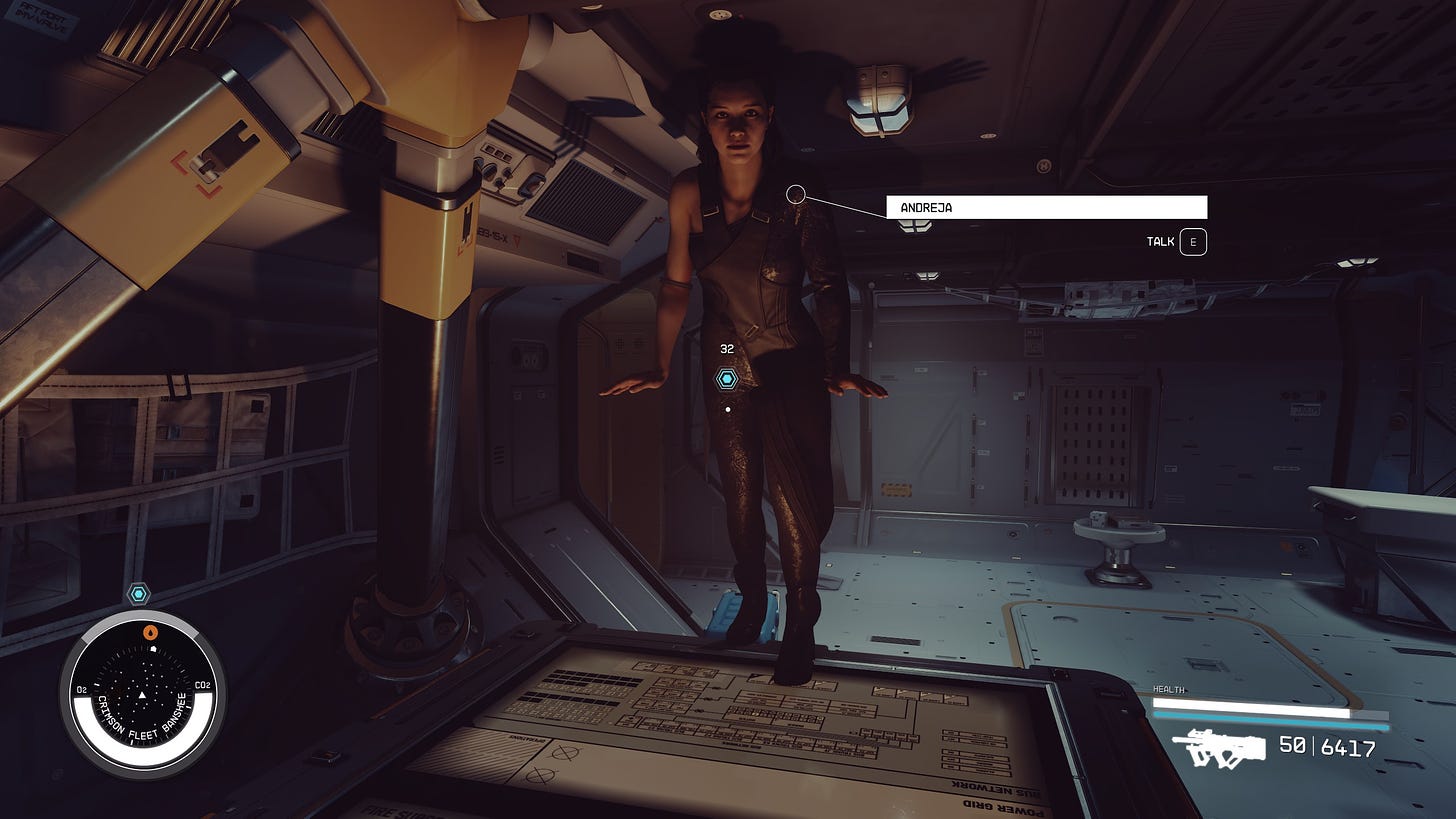

Game #2 can be pretty good. The start and end of the UC Vanguard and Crimson Fleet questlines are fun, even if they both have a bunch of filler in the middle of the chain. I love the first walk you take around the game’s big cities where you meet all the different people with problems. And I actually like the process of building and staffing up a big starship — I just wish they’d given your crew more to do or more interesting interactions with each other. There are some decent space encounters (the ECS Constant, Juno’s Gambit), but they always seem to peter out rather than coming to a point.

Can you come up with something truly nice to say about this game? They did a great job on the gun sounds, in my opinion. I holster and re-draw my gun a lot while people are talking just to hear the noise.

PY: Barrett, the companion who has spent the most amount of in-game hours under my dubious, manic leadership, put it best: “Every day that we all keep talking is a day we should celebrate.”1

When he said that, I immediately imagined that by “we” he meant “we NPCs.” I honestly cherish every moment Starfield has caused me to hemorrhage hee-haws at happy NPC accidents, those moments when they say their lines at weird times or in weird tones. I’ve taken way more 30-second clips of Starfield gameplay than I have any other game I’ve played this year, mostly capturing bizarre NPC interactions or glitches. Pete Hines recently claimed that Bethesda “embraces the chaos” when it comes to bugs and jank. I’m inclined to defend him on that; I find some of Bethesda’s signature quirks to be charming, even when unintentional.

I think I’ll always be a lover-hater of Bethesda’s work. I entered Starfield with tempered expectations, and if I’m being honest, the game actually delivered more than what I expected. Nowadays, playing a Bethesda game is sort of like going to see the new M. Night Shyamalan movie in theaters with a group of friends; a part of the fun is performing detailed autopsies on their unique failures, comparing notes on old-fashioned Bethesda hiccups that you’ve all spotted during your hundreds of hours of playing their games. But I was genuinely surprised at some of the twists and turns that questlines took. As you noted, the UC Vanguard and Crimson Fleet questlines were particularly rich in both story and action.

For all the grievances I had with Starfield, it never occurred to me to stop playing it altogether, even with this year’s steep backlog. It still holds me in its crude Terrormorph grip well into the late hours of the night. I’m honestly jealous of the amount of ground you’ve covered thus far; I’m still grinding for that coveted Class C license, gluing cargo containers to the Razorleaf like it’s a shipping yard katamari.

CB: I still think it sucks! But I don’t want to spray acid all over the end of this discussion. Bethesda’s games usually age well, and Starfield’s inevitable “one good DLC” and its real mod tools aren’t even out yet. Modders like the Sim Settlements crew are the reason I’ve got more than 100 hours in Fallout 4; for better and worse, they do what Bethesdon’t.

This is said seemingly apropos of nothing during a questline that doesn’t necessitate diplomacy, by the way.