When an editor at Vulture asked me if I had any ideas for interviews to accompany their list of the 100 hardest videogame levels, I immediately thought of Bennett Foddy. I interviewed him years earlier for the A.V. Club (RIP) as part of a series documenting the creation of pivotal indie games. He walked me through the creation of internet-legend QWOP at length: how he stumbled upon game design while procrastinating from finishing his PhD in philosophy, his attitude toward comedy in games, and his broader opinions about “difficult art.” When I reached out to him again for the Vulture article, I said it was this last thread I’d like to pick up on, digging into his philosophy on prickly, frustration-inducing video games.

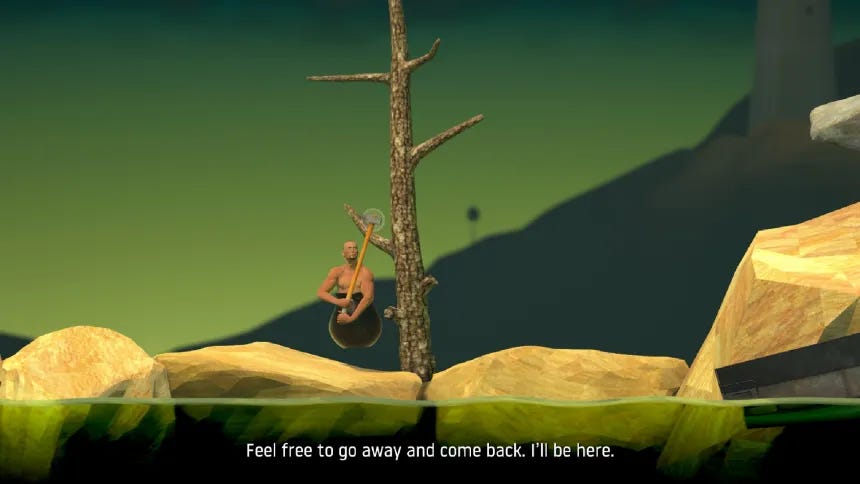

In the years between our interviews, Foddy has become synonymous with this sort of game. His 2017 effort Getting Over It With Bennett Foddy was an instant smash thanks in part to the heights of rage toward which it goaded many famous streamers. Foddy narrates throughout the game, gently cajoling the player after a miserable fall, but also elucidating a philosophy toward game design and difficulty that turns the absurd mission of the player — to climb up a mountain of garbage using only a hammer and maddeningly finicky rotating controls — into an almost religious odyssey.

For me, the conversation served double duty, in that I had recently noticed a concerning tendency in myself toward non-investment in games: beelining for walkthroughs, eyeing difficulty settings yearningly, bailing at a second’s inconvenience. Why was I giving games short shrift?

It was a great chat, much of which didn’t make it into the ensuing article, so I asked Foddy if I could reprint it here. It’s become more timely, in a way. In June, Foddy announced Baby Steps, an upcoming game made alongside the team behind Ape Out. And over the past couple of months, a low-rent Foddylike called Only Up surged up the Steam charts, transplanting Getting Over It to three dimensions but lacking its sense of intentionality.

Anyway, our conversation was before either of those, but it applies across them all. The thing I found is that his approach toward difficulty is less death-metal than it all seems. It’s less about getting over some mountain than it is about getting over ourselves.

Here's an edited-down version of our hour-long chat.

EX: Do you remember when you realized you had a particular taste for difficult games?

BF: I grew up on difficult video games. Being somebody who was a kid in the ‘80s, they just were very difficult. And so to love video games was to love difficult video games. I didn't start making games until I was about 30. That was right about when the cultural norms shifted around games. I come in as a 27-year-old relic, carrying in tastes and preferences that are out of step with what people are expecting and what they're playing at that time. I'm going to attune it to my own taste, especially my taste in short-form, arcade-style experiences. It's going to just be hard, right?

I got started making Flash games. You have to have a very small downloadable and you have somebody for a very limited window of attention. It’s very similar to what you had with early arcade machines. They made those hard because they had to be. Carrying my childhood taste into the era of Flash games felt very natural.

Now, why do people say that they’re hard? Let's say QWOP is difficult and Robot Unicorn Attack, which is a contemporary, with a similar level of popularity. Nobody says, “Oh, Robot Unicorn Attack, what a difficult game.” But from my point of view, it's more difficult. It's twitchy. It's more punishing.

The thing that I eventually came to realize is that it's all about people's expectations. Everything when you're talking about difficulty in games has to be framed in terms of, how do people expect this run to go? And how did it actually go? And are the points of difficulty in the places where I expected them to be? A game is marked out as hard if you expected to be able to do things and you couldn't do them. And it is marked out as easy if the things you expect it to be able to do you could do even if there's a lot of repetition.

EX: QWOP sets that up so well. Here's a person who's ready to run and then they tip slowly backwards. That expectation immediately biffs.

BF: That's the whole joke of QWOP, right? I'm going to deliberately set up an expectation that this is going to be easy in the way you would expect it to be easy. This here is kind of a geometrically simple task, and a verb that you're normally given automatically in a video game. This should be as easy as holding the right key on your keyboard.

EX: What do you think the appeal is of a list of difficult games? I can’t imagine a list of “most difficult movies,” but it seems organic with games.

BF: Movies can be difficult, right? It might be tough to hold your attention, might be tough to stay awake. It can be tough to make sense of, it can be emotionally difficult to watch. Those are the ways in which it's difficult. Passive forms of difficulty, I suppose. But it's not what's prized in those movies. It's more like the thought is well, it's worth suffering through the boredom of this movie, because the revelation that will give you, the beauty that it provides, is worth it.

Whereas in games, it's a bit more essential to the experience. Battletoads is such an interesting classic exemplar of a difficult game because you couldn't say, “I'm going to try to get through the difficulty in order to get the beautiful meat of Battletoads.” It's not the hard part around a succulent meat. People are playing Battletoads for the part that is difficult. Nobody's in it for the graphics anymore. Nobody's in it for the storytelling or the characters. It's the gameplay.

And again, what do I mean by hard? What I mean is, it's a mascot platformer in an era of mascot platformers in which you could pretty much get to the end. It’s not like Mario Brothers 3 or Sonic the Hedgehog are easy games to get to the end of, but little kids can at least get some levels into those games. And with enough perseverance can definitely get to the end. Battletoads might have been their first experience with a game in this genre, where that's the expectation that they couldn't get to the end of even after hours and hours and hours of trying. Partly because of its structure. That infamous hoverbike section on the tunnel section — It's not actually that hard. I played [it] on a Kotaku stream a couple of years ago. We got through it. If you can jump into that section, it's fine. But if you're tilting, because you've just spent hours and hours playing a totally different game and then you have to do this thing — then it's hard.

But anyway, it's so different than film. It's clearly something that we prize in the experience. It's a flavor that people are attracted to.

The friction in games is really a lot of what they're made of.

EX: It’s a little more elemental in games. You can “beat” a 10-hour movie by just sitting there. You can read a huge book without understanding it.

BF: But what if there was a movie that if you weren't understanding it, it would stop? I would argue that if we had a movie that checked in on you every 10 minutes to see if you're understanding it, it would be a video game. Almost by definition. There is something there, even for easy games. The friction in games is really a lot of what they're made of.

EX: I’ve noticed a theme of authorship in your games — your name is directly in the title of two of them, for example. In the trailer for Getting Over It, you say “I made this game for a certain type of person. To hurt them.” What do you think is the relationship between author and player specifically in a difficult game?

BF: Getting Over It’s authorship is about two things. The first is it was coming out in a post-Gamergate world. There was a lot of oppositionality between players and developers. A lack of understanding. I was concerned about a growing consumerist stance, which you could see in TotalBiscuit videos and Steam forums and so on, of treating the developer as a purveyor of a service. Like “lazy devs” — that kind of idea. One of the central projects of indie games writ large is the idea that you're able to deindustrialize games. Treating it as a product of a human being. Playing a game should feel like you're in dialogue with human beings. I had been inspired by Davey Wreden and Nina Freeman and their games, which had this visible author.

The other thing that my presence in that game does is frame the experience for people. So if I say that people only say QWOP is a difficult game because they carry in this frame where this activity should be easy. But the way we play any game — really come to any kind of art — we carry in a lot of baggage and there's a lot of conveyance that needs to happen. If somebody is to come out of a David Lynch movie and say, “I thought that was terrible. I didn't understand any of what happened.” We don't say “Oh, you idiot,” you know? We say, “That's okay. You’re not supposed to get it all. It's meant to be like an onion and you get little threads and it's a puzzle that you think about and it never really coheres into a narrative or a message or philosophy. It's supposed to be tangled and and it rewards playful thinking.”

I wanted to do something like that in the text. So the idea was, “What's the experience meant to be?” The experience of playing Getting Over It is meant to be that you strive to make progress. And then you lose some and you feel that frustration, that loss intensely. You meditate on what that's like to overcome that. I want to give you that as the experience. I know not everybody wants it. That's totally fine. But it's not an accident that it's coming out that way, right? If I've only played real progress-forward games like JRPGs or Ubisoft open-world games where you really can't lose progress at all, and then I come into this and it's not framed for me, I just think it's broken. I'm like, why doesn't this have save points? Why doesn't this have quick reload?

If you want to have a game that has lost progress, that has to be conveyed to the player, they have to understand that that's part of the point. And so in a way everything about Getting Over It is about conveying that to the player. The marketing is like that. The script is like that. The presence of the author is like that. The fun here, the enjoyment, the meat of the experience is in losing progress. And I think that worked. I mean, I think people got it.

EX: Were you nervous at all to make “Bennett Foddy” a character? Did it feel weird to abstract yourself and make yourself the antagonist of the game?

BF: I've been experiencing that for a long time. People started to frame QWOP as a difficult game. That's an easy character to enjoy: playing the sadistic game designer. Game designers all are a little bit sadistic in that way. At least I haven't met any who don't have at least a little streak of finding it funny when players have a hard time. I got an email the other day that just said, “I hope you step on a Lego.”

Is it scary to make it your actual self? I don't know. For me, as somebody who grew up as a kid with a very strange name thanks to my parents, it's cathartic. Being in public I had difficulty introducing myself to the class because they would laugh at my stupid name. To grow up essentially is about overcoming those sorts of things. A lot of indie game developers have an impulse to hide their identity. Of course, some people have used a pseudonym, and I have that impulse too. I'm sympathetic to it, and I know it’s not even optional for everyone, but for me it feels like something that I need to push through and overcome.

There's a point of finding your zen that you can come to through an extreme moment of non-zen.

EX: As a writer, I think a lot about audience. There are people I've been writing to my whole career. Who is that type of player that you made Getting Over It for? Are there specific people that you're thinking of?

BF: There are a few different types of people that I'm thinking about. The most obvious one who comes to mind is the player who has to win 100% every game. Where they think, “Part of my understanding of myself is that I'm good at games. And when I play a game I beat it easily, doesn't matter how hard it is.” It's interesting to me to humble players who have never had to be humbled. They realize, “It’s ok to be bad at something. I actually can get better at this thing, however gradually that might be.” I hear from a certain number of players who feel like they learned something about perseverance.

And then there's also players who get very angry upon losing progress. That's not a very big segment of the population, but there are definitely people like that and we all know them. Sore losers, if you like. I've heard from a certain number of appreciative sore losers over the years who have been like, “Oh, this changed something in me. At some point, my sense of rage evaporated, and I found a sense of calm.” I'm really interested in that. That’s a cool outcome. Growing up playing very difficult games did something similar to me at an early age. There's a point of finding your zen that you can come to through an extreme moment of non-zen.

We're also in this weird era where a lot of people are playing games, not in the way that I played them, but in a way where they watch somebody play it and react. And they want to taste what that person was feeling when they were playing the game in order to connect with them. That's not something I designed it with. But that ultimately became a huge part of the audience.

EX: You mentioned Gamergate earlier. After it, difficulty became a sort of gatekeeping thing for some self-identifying gamers. How do you feel about the “git gud” discourse?

BF: I mean, the game is also for them. But I didn't want to make it a game that was espousing that ideology. In fact, I rewrote the script, because my friends who were playing it were reporting that it had too much of a “git gud” feeling about it in the first draft.

Of course, that frame hangs over a game like this. Some of the script is asking people to interrogate what they're doing when they're playing a difficult game and to admit to themselves that it's the friction and the failure that's attractive and not the success. That's what the script is asking, especially towards the end. It's working on the assumption that there is a certain degree of failure involved.

I am not good at games. I'm not good at Getting Over It. When I was testing it, I was getting through it in six hours. I have never been really good at games. Telling people to “git gud” is the last thing that's on my mind. It’s more of a “get bad” ideology. I want people to feel like I do when I'm playing a difficult game, which is that I'm having a good time despite being really terrible at it. That's the feeling that I wanted to convey.

Hopefully that speaks to people who are normally into that toxic “git gud” thing, it gives them a slightly different experience. But also to people who are on the other side of that, like I am. Doesn't matter how much I practice Bloodborne, I'm never going to be able to do that parry. In Bloodborne I spent hours and hours and hours trying to learn that thing. It's just not in me. It's not happening.

EX: I relate. I beat Elden Ring recently, but it was with very little integrity.

BF: Exactly, same. If I can find an exploit in those Souls games, I'm taking it.

EX: I've been playing Sekiro lately, too, which is similar to Getting Over It in that it gives you no outs. Getting Over It has been helpful in teaching me to embrace it. Just let the fall happen.

BF: There's a feeling of drawing on a resource that you have but can't comfortably access. The one that springs to mind for me is Steven’s Sausage Roll, a very difficult puzzle game. When I'm playing any puzzle game, I bring mild creative logical thinking. I bring maybe 5% of that brain. And once that's exhausted, I go straight to the brute force method. Steven’s Sausage Roll gives you nothing for brute force. Until you start thinking seriously, you're not making progress in that game. It was that sense of being forced to really think, once I'd made a decision in my heart to play it and to get through it. Being forced to really think was beautiful. I can only do this in small doses, but I'm going to actually problem solve here.

EX: This gets back to what we were talking about earlier, but a difficult game forces you to get on its level. If you're reading Ulysses, you don't need a PhD in mythology and history to read the book. You can just keep reading the words. But with a game you do have to grok it.

BF: Frank Lantz has a book coming out that I have read a draft of. It's based off of his GDC talks. He has this talk called “Hearts and Minds” that's a little bit about QWOP and about what the experience of playing QWOP is like. For him a lot of this stuff is about metacognition. Looking inward on the process of learning to play a video game — on what it feels like — is a lot of what playing a video game is about.

I've been playing a work in progress game by some friends recently that's very difficult. I'm looking inward on this experience of playing it. This game is a really good choke machine. Games can make you start to tilt and become self-conscious and to choke. Getting Over It is an excellent choke machine. You can take somebody who's normally very calm and very clutch. If they practice something then they can reproduce it perfectly. But there are certain ways that you can create an experience that brings people more to that level of like, “Am I actually gonna be able to do this? Now I'm starting to tilt — Oh, fuck, now I'm tilted. Now I can't do it at all.”

I love that because I'm such a chokey person. It's one of the reasons that I have so much difficulty getting good at games is because I tend to be really unclutch. As soon as the pressure starts to come up, or as soon as I start to tilt, it's just over. I love that feeling. Bringing it out in people is really interesting to me. And I think that there is something very beautiful in choking which is that people are aware of it almost all the time. They can feel it start. They can feel it really take hold and they can't really do much to stop that happening.

Channeling Frank's talk, that's the essence of what's good about games. The sense of like, “I've become aware of what's happening in my mind right now. And I'm seeing it reflected through what's happening on the pixels onscreen coming through my hands on the controller, and that's giving me a little window into what's going on with me. I'm choking. I'm trying to stop choking and it's not working and the more I try to stop choking the more I'm choking.”

EX: You did an interview with Jesper Juul where you talk about “disobedience” in games. It’s been a very helpful idea for me. How did that idea emerge for you over time?

BF: Let's look at what the average video game does these days. Let's say a modern Assassin's Creed is the most emblematic game of our era. It’s got a lot of activities. It's got some crafting systems, got exploration. More importantly than anything, it's got these very, very deep, complicated progression systems and everything has this, from God of War to Elden Ring, whatever it might be. Nearly everything has a progression system.

You can fail a mission, be sent back, you can die, then wake up in a hospital. They have friction in that sense. But they also have this little ratchet of progress. Even when we fail, we ratchet a little progress. What it's doing is making the task I'm trying to repeat get easier on each repetition, because my character gets more powerful. Sooner or later, I'm going to tip over into being able to make progress. Although there's friction, there's not that much friction. It's lubricated in a certain way.

The point that I was trying to get across to Jesper is that when a video game guarantees you progress, there's a subservience in that stance. It's the subservience of the software to the player, for sure, but really, more importantly, it's a subservience of the designer to the player in a way that I don't think that novelists do, or filmmakers or musicians do, because they're not involved in the same direct interplay with the behavior of their audiences. You write something as a writer, you hope to tailor it for an audience and so on. But if it's not working great for them, it's not like the piece of writing can go and dumb itself down a bit. It's just out there. Whereas in games, we have this different thing where we’re able to make the game kind of gradually surrender to the player.

And I probably would be so into that if it was unusual and counter to the norms, but in fact the absolute monolithic mainstream is that games are subservient. It's interesting to me to explore, “What does it look like for games to assert themselves?” It's the designer asserting themselves through the game. They're trying to say, “Well, you know, no, this is not a thing where I'm serving you. Where I'm your servant, and this is a service relationship and the customer is always right. And I have to, I have to keep the customer happy by giving them little bits of progress. This is a thing where two equals a meeting.”

EX: What does disobedience excuse? Does it excuse anything that isn't what the player wants? Does it excuse jank?

BF: That's different. Disobedience should at least feel intentional. I don't think disobedience excuses design failures in general. I do think that doing something contrary to what the player wants you to do is an interesting lever that you can use thoughtfully and intentionally and that hopefully the player understands.

Maybe the goal is to make sure that the player grasps that this disobedience is intentional. Great example from the world of difficulty in games is the question of the checkpoint. Some games save your every pixel of movement. Some games require you to get to a checkpoint in order to save them. What you create is a cadence of stress where after I hit a checkpoint, I'm relaxed. And the further I get without getting to the next checkpoint, the more stressed I am because I stand to lose more. And so the spacing of the checkpoints is a creative tool that the designer has to be able to change the cadence of stakes that the player feels as they're playing.

It's interesting to me to explore, “What does it look like for games to assert themselves?”

EX: In that Jesper Juul interview, you say, “It's one of my strongest moral aesthetics that the player should not be the owner of the game.” Is that moral position inherent to disobedience in games?

BF: Just in thinking about the oppositional consumerist pose, the posture that some gamers sometimes take, you know, which we see in the cliche of “lazy devs,” right. That's a failure in the culture when that happens. It's not only a failure of the player. It's a failure of the designer to escape that modality as well. It's a bilateral failure for the designer and the player to meet on an understanding that this is an intentional work of art by a human being and instead to treat it like it's a functional plastic tool made in a factory that is there to generate a particular biochemical response in your brain. That's to the diminishment of the medium. The more that it is treated like a tool for generating fun or engagement or to pass time, the more that it’s instrumentalized in that way, the less it's a creative, artistic form.

Games, just like any other creative medium, should be more than that, or should at least be able to be more than that. I definitely don't think it's wrong to try to make a game that is purely a fun machine. I think that's totally fine. But at least the culture should make room for the players to understand this other experience, that is not simply treating it as a machine that needs to do certain things but instead treating it as a dialogue between an author and the audience. When we get locked in that consumerist stance, we're stuck in the other way of looking at it. It ceases to be a creative medium at that point, and it starts to be just software. For me, that's a strong enough aesthetic stance to be a moral stance.